I’ve been confused about what’s going on with terminals for a long time.

But this past week I was using xterm.js to display an

interactive terminal in a browser and I finally thought to ask a pretty basic

question: when you press a key on your keyboard in a terminal (like Delete, or Escape, or a), which

bytes get sent?

As usual we’ll answer that question by doing some experiments and seeing what happens :)

remote terminals are very old technology

First, I want to say that displaying a terminal in the browser with xterm.js

might seem like a New Thing, but it’s really not. In the 70s, computers were

expensive. So many employees at an institution would share a single computer,

and each person could have their own “terminal” to that computer.

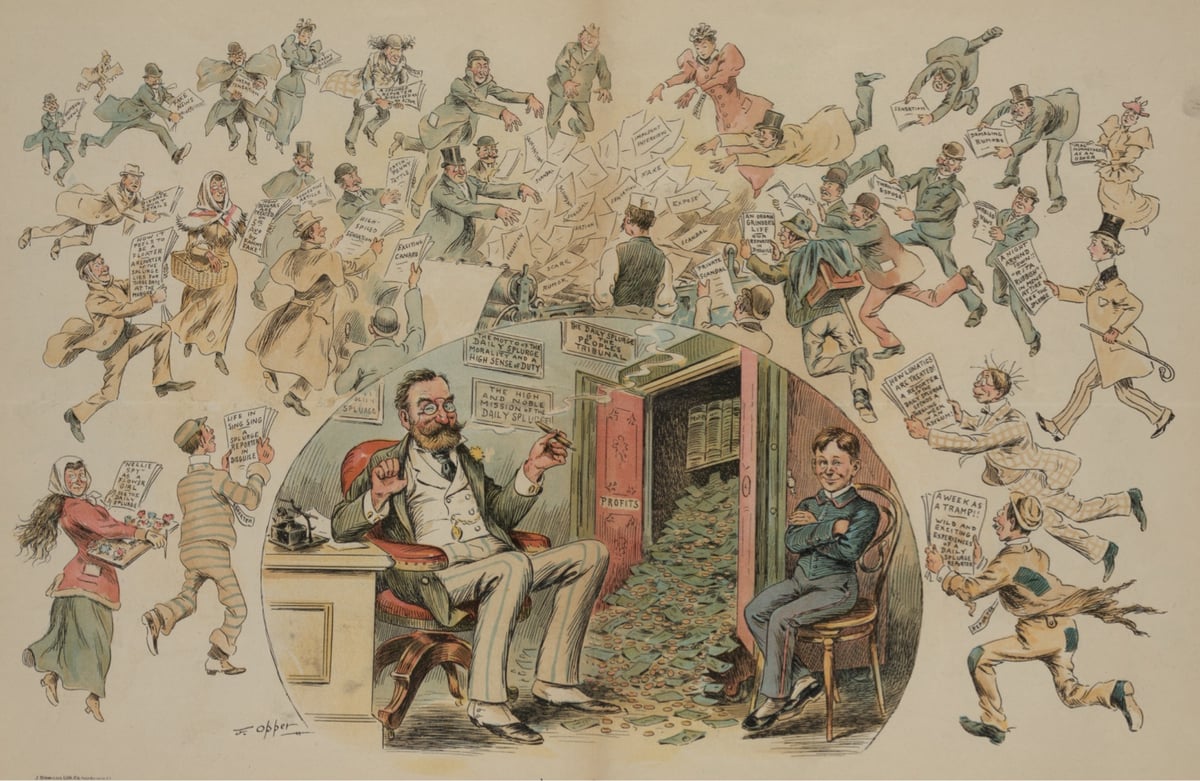

For example, here’s a photo of a VT100 terminal from the 70s or 80s. This looks like

it could be a computer (it’s kind of big!), but it’s not – it just displays

whatever information the actual computer sends it.

Of course, in the 70s they didn’t use websockets for this, but the information

being sent back and forth is more or less the same as it was then.

(the terminal in that photo is from the Living Computer Museum in Seattle which I got to visit once and write FizzBuzz in ed on a very old Unix system, so it’s possible that I’ve actually used that machine or one of its siblings! I really hope the Living Computer Museum opens again, it’s very cool to get to play with old computers.)

It’s obvious that if you want to connect to a remote computer (with ssh or

using xterm.js and a websocket, or anything else), then some information

needs to be sent between the client and the server.

Specifically:

- the client needs to send the keystrokes that the user typed in (like

ls -l)

- the server needs to tell the client what to display on the screen

Let’s look at a real program that’s running a remote terminal in a browser and see what information gets sent back and forth!

we’ll use goterm to experiment

I found this tiny program on GitHub called

goterm that runs a Go server that lets you

interact with a terminal in the browser using xterm.js. This program is very insecure but it’s simple and great for learning.

I forked it to make it work with the latest xterm.js,

since it was last updated 6 years ago. Then I added some logging statements to

print out every time bytes are sent/received over the websocket.

Let’s look at sent and received during a few different terminal interactions!

example: ls

First, let’s run ls. Here’s what I see on the xterm.js terminal:

bork@kiwi:/play$ ls

file

bork@kiwi:/play$

and here’s what gets sent and received: (in my code, I log sent: [bytes] every time the client sends bytes and recv: [bytes] every time it receives bytes from the server)

sent: "l"

recv: "l"

sent: "s"

recv: "s"

sent: "\r"

recv: "\r\n\x1b[?2004l\r"

recv: "file\r\n"

recv: "\x1b[?2004hbork@kiwi:/play$ "

I noticed 3 things in this output:

- Echoing: The client sends

l and then immediately receives an l sent

back. I guess the idea here is that the client is really dumb – it doesn’t

know that when I type an l, I want an l to be echoed back to the screen.

It has to be told explicitly by the server process to display it.

- The newline: when I press enter, it sends a

\r (carriage return) symbol and not a \n (newline)

- Escape sequences:

\x1b is the ASCII escape character, so \x1b[?2004h is

telling the terminal to display something or other. I think this is a colour

sequence but I’m not sure. We’ll talk a little more about escape sequences later.

Okay, now let’s do something slightly more complicated.

example: Ctrl+C

Next, let’s see what happens when we interrupt a process with Ctrl+C. Here’s what I see in my terminal:

bork@kiwi:/play$ cat

^C

bork@kiwi:/play$

And here’s what the client sends and receives.

sent: "c"

recv: "c"

sent: "a"

recv: "a"

sent: "t"

recv: "t"

sent: "\r"

recv: "\r\n\x1b[?2004l\r"

sent: "\x03"

recv: "^C"

recv: "\r\n"

recv: "\x1b[?2004h"

recv: "bork@kiwi:/play$ "

When I press Ctrl+C, the client sends \x03. If I look up an ASCII table,

\x03 is “End of Text”, which seems reasonable. I thought this was really cool

because I’ve always been a bit confused about how Ctrl+C works – it’s good to

know that it’s just sending an \x03 character.

I believe the reason cat gets interrupted when we press Ctrl+C is that the

Linux kernel on the server side receives this \x03 character, recognizes that

it means “interrupt”, and then sends a SIGINT to the process that owns the

pseudoterminal’s process group. So it’s handled in the kernel and not in

userspace.

example: Ctrl+D

Let’s try the exact same thing, except with Ctrl+D. Here’s what I see in my terminal:

bork@kiwi:/play$ cat

bork@kiwi:/play$

And here’s what gets sent and received:

sent: "c"

recv: "c"

sent: "a"

recv: "a"

sent: "t"

recv: "t"

sent: "\r"

recv: "\r\n\x1b[?2004l\r"

sent: "\x04"

recv: "\x1b[?2004h"

recv: "bork@kiwi:/play$ "

It’s very similar to Ctrl+C, except that \x04 gets sent instead of \x03.

Cool! \x04 corresponds to ASCII “End of Transmission”.

what about Ctrl + another letter?

Next I got curious about – if I send Ctrl+e, what byte gets sent?

It turns out that it’s literally just the number of that letter in the alphabet, like this:

Ctrl+a => 1Ctrl+b => 2Ctrl+c => 3Ctrl+d => 4- …

Ctrl+z => 26

Also, Ctrl+Shift+b does the exact same thing as Ctrl+b (it writes 0x2).

What about other keys on the keyboard? Here’s what they map to:

- Tab -> 0x9 (same as Ctrl+I, since I is the 9th letter)

- Escape ->

\x1b

- Backspace ->

\x7f

- Home ->

\x1b[H

- End:

\x1b[F

- Print Screen:

\x1b\x5b\x31\x3b\x35\x41

- Insert:

\x1b\x5b\x32\x7e

- Delete ->

\x1b\x5b\x33\x7e

- My

Meta key does nothing at all

What about Alt? From my experimenting (and some Googling), it seems like Alt

is literally the same as “Escape”, except that pressing Alt by itself doesn’t

send any characters to the terminal and pressing Escape by itself does. So:

- alt + d =>

\x1bd (and the same for every other letter)

- alt + shift + d =>

\x1bD (and the same for every other letter)

- etcetera

Let’s look at one more example!

example: nano

Here’s what gets sent and received when I run the text editor nano:

recv: "\r\x1b[Kbork@kiwi:/play$ "

sent: "n" [[]byte{0x6e}]

recv: "n"

sent: "a" [[]byte{0x61}]

recv: "a"

sent: "n" [[]byte{0x6e}]

recv: "n"

sent: "o" [[]byte{0x6f}]

recv: "o"

sent: "\r" [[]byte{0xd}]

recv: "\r\n\x1b[?2004l\r"

recv: "\x1b[?2004h"

recv: "\x1b[?1049h\x1b[22;0;0t\x1b[1;16r\x1b(B\x1b[m\x1b[4l\x1b[?7h\x1b[39;49m\x1b[?1h\x1b=\x1b[?1h\x1b=\x1b[?25l"

recv: "\x1b[39;49m\x1b(B\x1b[m\x1b[H\x1b[2J"

recv: "\x1b(B\x1b[0;7m GNU nano 6.2 \x1b[44bNew Buffer \x1b[53b \x1b[1;123H\x1b(B\x1b[m\x1b[14;38H\x1b(B\x1b[0;7m[ Welcome to nano. For basic help, type Ctrl+G. ]\x1b(B\x1b[m\r\x1b[15d\x1b(B\x1b[0;7m^G\x1b(B\x1b[m Help\x1b[15;16H\x1b(B\x1b[0;7m^O\x1b(B\x1b[m Write Out \x1b(B\x1b[0;7m^W\x1b(B\x1b[m Where Is \x1b(B\x1b[0;7m^K\x1b(B\x1b[m Cut\x1b[15;61H"

You can see some text from the UI in there like “GNU nano 6.2”, and these

\x1b[27m things are escape sequences. Let’s talk about escape sequences a bit!

ANSI escape sequences

These \x1b[ things above that nano is sending the client are called “escape sequences” or “escape codes”.

This is because they all start with \x1b, the “escape” character. . They change the

cursor’s position, make text bold or underlined, change colours, etc. Wikipedia has some history if you’re interested.

As a simple example: if you run

echo -e '\e[0;31mhi\e[0m there'

in your terminal, it’ll print out “hi there” where “hi” is in red and “there”

is in black. This page has some nice

examples of escape codes for colors and formatting.

I think there are a few different standards for escape codes, but my

understanding is that the most common set of escape codes that people use on

Unix come from the VT100 (that old terminal in the picture at the top of the

blog post), and hasn’t really changed much in the last 40 years.

Escape codes are why your terminal can get messed up if you cat a bunch of binary to

your screen – usually you’ll end up accidentally printing a bunch of random

escape codes which will mess up your terminal – there’s bound to be a 0x1b

byte in there somewhere if you cat enough binary to your terminal.

can you type in escape sequences manually?

A few sections back, we talked about how the Home key maps to \x1b[H. Those 3 bytes are Escape + [ + H (because Escape is

\x1b).

And if I manually type Escape, then [, then H in the

xterm.js terminal, I end up at the beginning of the line, exactly the same as if I’d pressed Home.

I noticed that this didn’t work in fish on my computer though – if I typed

Escape and then [, it just printed out [ instead of letting me continue the

escape sequence. I asked my friend Jesse who has written a bunch of Rust

terminal code about this and Jesse told me

that a lot of programs implement a timeout for escape codes – if you don’t

press another key after some minimum amount of time, it’ll decide that it’s

actually not an escape code anymore.

Apparently this is configurable in fish with fish_escape_delay_ms, so I ran

set fish_escape_delay_ms 1000 and then I was able to type in escape codes by

hand. Cool!

terminal encoding is kind of weird

I want to pause here for a minute here and say that the way the keys you get

pressed get mapped to bytes is pretty weird. Like, if we were designing

the way keys are encoded from scratch today, we would probably not set it up so

that:

Ctrl + a does the exact same thing as Ctrl + Shift + aAlt is the same as Escape- control sequences (like colours / moving the cursor around) use the same byte

as the

Escape key, so that you need to rely on timing to determine if it

was a control sequence of the user just meant to press Escape

But all of this was designed in the 70s or 80s or something and then needed

to stay the same forever for backwards compatibility, so that’s what we get :)

changing window size

Not everything you can do in a terminal happens via sending bytes back and

forth. For example, when the terminal gets resized, we have to tell Linux that the window size has

changed in a different way.

Here’s what the Go code in

goterm

to do that looks like:

syscall.Syscall(

syscall.SYS_IOCTL,

tty.Fd(),

syscall.TIOCSWINSZ,

uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(&resizeMessage)),

)

This is using the ioctl system call. My understanding of ioctl is that it’s

a system call for a bunch of random stuff that isn’t covered by other system

calls, generally related to IO I guess.

syscall.TIOCSWINSZ is an integer constant which which tells ioctl which

particular thing we want it to to in this case (change the window size of a

terminal).

this is also how xterm works

In this post we’ve been talking about remote terminals, where the client and

the server are on different computers. But actually if you use a terminal

emulator like xterm, all of this works the exact same way, it’s just harder

to notice because the bytes aren’t being sent over a network connection.

that’s all for now!

There’s defimitely a lot more to know about terminals (we could talk more about

colours, or raw vs cooked mode, or unicode support, or the Linux pseudoterminal

interface) but I’ll stop here because it’s 10pm, this is getting kind of long,

and I think my brain cannot handle more new information about terminals today.

Thanks to Jesse Luehrs for answering a billion of my questions about terminals, all the mistakes are mine :)